Jaki Shelton Green becomes N.C.’s poet laureate

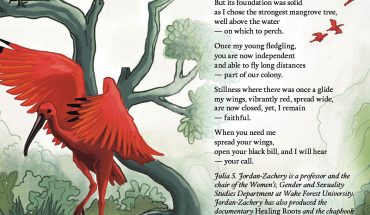

by Chris Vitiello | Photography by S.P. Murray

For North Carolina’s new state Poet Laureate, the literary life started while squirming in her Sunday best on a church pew.

“I was not unruly, but very fidgety, in church because I was fascinated by people and I wanted to turn around and stare at them,” Jaki Shelton Green says. “I wanted to ask my grandmother and my mother a thousand questions, and they were like ‘Shhhh! Be quiet!’ So my grandmother gave me these tiny tablets, and they had little pencils that came with them. My grandmother literally had a score of them. And that was my Sunday treat. That and a stick of spearmint gum, and I was good for hours.”

Scribbles turned into letters and words. Green wrote descriptions of women’s hats and stories about church elders. Her fascination with the act of communion, and the resonance between the words “blood” and “bread,” found its way into nickel notebook after nickel notebook.

Green, 65, is North Carolina’s ninth poet laureate, and the first African American person to hold the position. She grew up in Efland, North Carolina, in Orange County, and is one of the most travelled and decorated poets in the state, serving as the first Piedmont Laureate in 2009 and winning the North Carolina Award for Literature in 2013. She was inducted into the state Literary Hall of Fame in 2014, and has published eight books of poetry, including Conjure Blues and Breath of the Song: New and Selected Poems through Carolina Wren Press and I Want to Undie You, an elegy for her daughter Imani, through Jacar Press in 2017. She currently teaches at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University and has taught writing workshops in various institutions for decades.

For Green, writing poetry has always been more about knowing and healing than publishing and teaching. As a child, writing gave her a platform to explore her curiosity, and as a young adult in the turbulent 60s and early 70s, it gave her a way to process the world and find her place in it. Away from home at boarding school in Pennsylvania, she took writing much more seriously.

“It was the civil rights movement, it was Vietnam and Cambodia,” she says. “I was asking questions about my identity, what it meant to be black and southern in America. And I’m this little militant being that my family doesn’t necessarily know what to do with. Writing became my container for helping me tease through a lot of the questions that I had.”

Officially, the poet laureate’s two-year appointment is to be spent giving readings, conducting programs and workshops, and writing occasional poems to commemorate events like inaugurations and the openings of civic buildings. But Green feels her purpose is much longer and larger than that.

“I encounter communities of people who have no idea what the poet laureateship is and what it can mean to them specifically. They tell me their stories, but do not necessarily feel that their stories are worthy of a greater literary context,” Green says.

“So, for me, my job is to be in these community centers, these small libraries, community colleges off the beaten track, in low-wealth communities. To remind them that we have always told stories and shared each other’s stories, and to sort of renew the energy inside of these communities. To bring them back to this vital practice, this traditional practice that we’ve sort of lost, especially in the South.”

Green’s poems frequently draw upon connections to place and memory. Memories and experiences often serve as opportunities for metaphor, instruction, and reflection. She finds higher levels of being in mundane events and familiar situations, and brings these levels out in rhythmic, lyrical language. Images and events resonate for readers and encourage them to find insight and profundity in their own experiences.

Green’s poem “i know the grandmother one had hands” lists ordinary memories of a grandmother that many people share—cooking, washing, mending clothes. But Green invests them with a heightened significance through her use of rhythm and repetition in the poem. The list becomes a litany, giving her final lines an emotional weight: “i know the grandmother one had hands / but they were always inside the clouds / poking holes for the / rain to fall.” Green sees her role as helping people all around the state recognize not only the legitimacy of their stories, but their own innate abilities to tell them and write them down—even if those stories are difficult or painful.

“Poets can take us to those dark places that that are hard to go to. Poetry can be such a neutralizer, such an equalizer,” Green says. “I think people are really looking for safer spaces where we can stand together, where we can cross boundaries, or we can erase both imaginary and real lines in the sand.”

For Green, poetry connects the everyday to the universal and helps people translate their unique experiences into lasting emotions that can be shared. She’s the right poet laureate for a politically divisive moment.

“We have to continue to make space at the table, you know? Writers have the power to make that table longer and wider. That’s how poetry helps lead us to do even more significant work. That’s how poetry becomes a governing force.”