“I find solace in looking at the landscape.

I think it’s a human thing. We all do.”

–John Beerman

by LIZA ROBERTS

photographs by LISSA GOTWALS

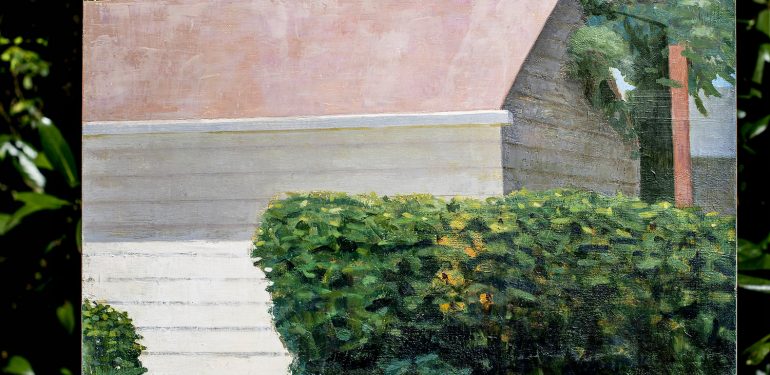

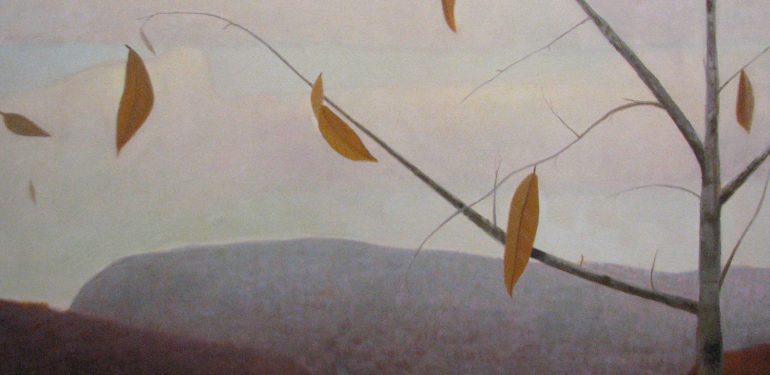

The 34 paintings currently on view at Lee Hansley Gallery in Raleigh – luminous, reverential landscapes and still lifes depicting North Carolina mountains, South Carolina beaches, Texas ranchland, and Tuscan hillsides – are the work of a transcendent depictor of light, a subtle student of color, a lover of nature.

John Beerman, lately of Durham, is the artist. “A master of the rural American sublime,” as Tibor de Nagy, Beerman’s gallery in New York, attests, Beerman was born and raised in Greensboro and lived for three decades on the Hudson River, steeping himself in the beauty of that valley and the work of the artists it spawned. But the South never really left him, and now that he has returned to it, his work shows the gentle influence of the nature, people, and rhythms of his home.

“You bloom where you’re planted, I guess,” says Beerman, 59, in his soft-spoken way. He has, after all, built a successful career by embracing his surroundings. His Hudson River landscapes and other works received acclaim early on, and have been exhibited widely in the United States and abroad. His paintings can be found in the collections of the North Carolina Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, and the governor’s mansions in New York and North Carolina, among many others.

Many here know him for his large-scale Three Trees, Two Clouds, which has hung at the NCMA for 25 years and “represents the apogee of North Carolina art at that end-of-the-20th-century period,” says NCMA director Larry Wheeler. “I think of John Beerman’s trees, and then I think of Van Gogh’s trees, and there’s a similarity, I must say.” The energy, physicality, spirituality, and surreal aspect of the work put Beerman on the map here, Wheeler says, and helped to make him one of North Carolina’s most prominently collected living artists.

Today, a well-rounded Beerman collection would have to include, in addition to the expansive landscapes, architectural studies and still lifes, too.

“His work is very mysterious, in a way,” says the author Frances Mayes, whose Hillsborough house and gardens, known as Chatwood, are often Beerman’s subject. “It has a kind of mythic element. He will paint a camellia on a branch, and it’s just a camellia. But isolated like that, and treated with such talent, and light, it becomes an icon.”

One recent Monday morning, Beerman was at the home he shares in Durham with his partner, the poet Tori Reynolds. It’s where he does most of his work these days. In a studio under the house, works in progress show how his painter’s eye has zoomed in on bits of the foreground that once gave way to the horizon’s sweep. Three poppies, a few lemons, a camellia. They seem to shimmer in focus, while behind them, almost blurred, lie the hillside, farm, or field that once would have filled his frame.

A painting, he says, always starts with good observation. “Your imagination is only as good as your observation. Once you stop observing, your imagination becomes cliché.”

His close-in observation can be seen in his paintings from the last couple of years, scenes painted at Mayes’s Hillsborough estate, and in and around her house in Tuscany. With invisible brushstrokes, expansive skies, and a restrained palette, the images appear to have arrived fully formed, outside time, trend, or influence. As a student, Beerman says he revered artists as diverse in subject, style, and era as the Dutch-American abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning (“before he got really abstract”) and the early Italian Renaissaince master Pierro della Francesca. “I have a thing for those wonderful old guys and the contemporary guys, and the mash-up of those two things.”

Most recently, Beerman’s focus and universe have become even more personal. “I’ve become more interested in … not about seeing new landscapes, but in seeing landscapes through new eyes,” he says. When his car broke down several months ago, he wanted to find out what it would be like to go without one. “I started discovering things right here on this property I had never noticed before,” he says. “The bark on trees – my God, this is amazing – and it’s just right here. And what I like about it is I can go out and look at it again in a different light. That’s the wonderful thing about nature. You think the tree is like this, and then it changes.” He found a tulip poplar around the corner in a neighbor’s yard and set up his easel to paint it. When the neighbor drove up and asked what he was doing, Beerman told him: “I hope you don’t mind,” he said. “I’m a painter, and I love your tree.”

“Great artists evolve,” says Wheeler. “As they grow older, their work becomes reduced to the fundamentals of their ideology. They often express their worldview more abstractly and more minimally; they come from a density to a minimalism.”

Early years

Beerman’s education as an artist began at boarding school in Vermont, where he learned photography and the value of self-direction. He began painting landscapes later, at the Rhode Island School of Design, inspired in part by an uncle who had painted on the deck in the summertime at Beerman’s grandparents’ house at Lake Toxaway in the Blue Ridge Mountains. At RISD, Beerman found a “phenomenal” teacher, Gerry Immonen, who encouraged him to stick to (then unfashionable) landscapes. “He opened up the world for me,” Beerman says. “He was the real thing. I still think about him every day.”

If Beerman is to be believed, he had to work harder than other students at RISD to find his way. And that fact, he says, has made his career. “The kids who came with all this talent, and it’s all so easy, don’t stay with it,” he says. “The ones like me – I like the work of it. It’s a lot of trial for me, and it’s a lot of error, and it’s mostly error, and I accept that. It’s a messy process.”

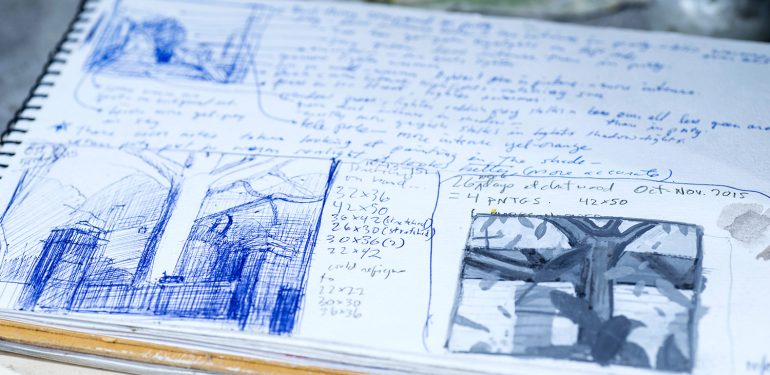

His pocket-sized studio, a cave of efficiency, betrays none of the mess, but it’s filled with the trials. Studies, sketches, notes abound. The same tulip, again, again, and again. Books – dog-eared, yellowed, annotated – on color. A meticulously crafted card of color triads. Notebooks and notes on light and shape and perspective. He makes his own gesso, his own egg tempera.

If nothing else, Beerman remains a dedicated student of his craft. His time spent studying, sketching, and writing is his way of navigating the images that shimmer in his mind’s eye. “It’s incredibly small,” he says, looking around the tiny space where he does all of this studying. “But it’s actually working for me.” He points out a simple easel perched at waist height. “The space that’s most important is the space between you and the canvas.” He reconsiders: “No. The space that is most important is the space between your ears.” Beerman once read a quote from the photographer Dorothea Lange on the virtues of getting lost in the studio. In it, he recognized himself: “I go in the studio, I get lost, and every so often, I get found again.”

Beerman found an important form of inspiration early on when he learned about the American Luminists, an 1850-1870 offshoot of the Hudson River School of artists who focused on the effect of light and tranquility in landscapes. Beerman was young, just out of school, and in the public library in East Hampton, N.Y. when he learned about their work. A series of Maine landscapes by Fitz Hugh Lane (also known as Fitz Henry Lane) gripped him. So inspired was Beerman that he borrowed his father’s camper van to drive up to Maine to seek out the spots Lane had painted nearly a century earlier. “Lo and behold, the landscape, the topography, was perfect,” Beerman recalls. “It was still essentially the same 100-odd years later.” But there was an important difference, too. The color, Beerman could see, had come not from nature, but from Lane’s own imagination.

It was an important realization: “It’s not all about observation. There’s this other component. It’s me. It’s personal.” The writings of Émile Zola, he says, also led him to believe that he had something to offer beyond craftsmanship: His sensibility. After that, he says, “I was on a mission.”

He put that mission to work in a studio he rented in East Hampton that had once belonged to the famed pop artist James Rosenquist; then he found his way upstate to Nyack, N.Y., where he worked for abstract expressionist Jasper Johns, who introduced him to the New York art world. He made prints in Nyack with his former mother-in-law, a printmaker, and had some chosen for a SoHo show that was reviewed in The New York Times. A solo show followed, which sold out. “It was very heady for me,” he says. “I can’t figure out if it’s a blessing or a curse to start out like that.”

Whatever the case, Beerman was in his element. Not only because he was surrounded in the Hudson River Valley by the subject of his artistic fascination, but because, as he learned after a full 25 years painting the river, he has a direct familial connection to the place: Henry Hudson himself is Beerman’s direct ancestor, his great-grandfather times six.

A similarly poignant and unexpected family connection to his surroundings greeted him when he returned to North Carolina six years ago. Mary Duke Biddle Trent Semans, the great-granddaughter of Washington Duke, for whom Duke University is named, bought a painting Beerman had done of Maple View Farm for the Duke Cancer Center. She told Beerman when she met him that his own great-grandfather, John Calvin Thorne, was a wonderful man she had never forgotten. She remembered well the time Thorne, who was the best friend and colleague of her own grandfather, Benjamin Duke, accompanied she and her mother on a transatlantic voyage at her grandfather’s behest. Most of a lifetime later, the Duke Endowment bought a large-scale Beerman landscape of the Ayr Mount estate in Hillsborough for its boardroom in Charlotte. Shortly after Semans died in 2012, Beerman visited the boardroom to see his painting. The only other art in the room was of Semans, whose portrait gazed upon it. The connection had come full circle. “It was a magical, sweet moment,” he says.

Magical connections seem to find Beerman. When he met a fleet of wonderful new friends including Frances Mayes shortly after arriving in Hillsborough, he also found an enduring source of artistic inspiration. Mayes feels the same way. “It’s so great to see him out in the garden at Chatwood,” she says. “With his straw hat, and his wooden easel, and two cats bothering him, oh, it’s like Monet at Giverny.” She has a few of his works, and would like to have more. “He can certainly pack a lot of power in a small painting, and his large paintings are so, so moving,” she says. “It will be interesting to see what he does next.”

One safe bet: He’ll do it in North Carolina. “I feel at home here,” he says, taking in the art-filled house he shares with Reynolds, the delicious lunch she has just prepared, the nature just outside the door. Back in the state of his birth, Beerman has found “a new life, a good life.”